Welcome to Algeria!

Algeria, large, predominantly Muslim country of North Africa. From the Mediterranean coast, along which most of its people live, Algeria extends southward deep into the heart of the Sahara, a forbidding desert where the Earth’s hottest surface temperatures have been recorded and which constitutes more than four-fifths of the country’s area. The Sahara and its extreme climate dominate the country. The contemporary Algerian novelist Assia Djebar has highlighted the environs, calling her country “a dream of sand.”

History, language, customs, and an Islamic heritage make Algeria an integral part of the Maghreb and the larger Arab world, but the country also has a sizable Amazigh (Berber) population, with links to that cultural tradition. Once the breadbasket of the Roman Empire, the territory now comprising Algeria was ruled by various Arab-Amazigh dynasties from the 8th through the 16th century, when it became part of the Ottoman Empire. The decline of the Ottomans was followed by a brief period of independence that ended when France launched a war of conquest in 1830.

History of Algeria

This discussion focuses on Algeria from the 19th century onward. For a treatment of earlier periods and of the country in its regional context, see North Africa.

From a geographic standpoint, Algeria has been a difficult country to rule. The Tell and Saharan Atlas mountain chains impede easy north-south communication, and the few good natural harbours provide only limited access to the hinterlands. This has meant that, before Ottoman rule, the western part of the country was associated more closely with Morocco while the eastern part had closer ties with Tunisia. A further impediment to unifying the country was that a significant minority of the population were native Tamazight speakers and were thus more resistant to Arabization as compared with North African countries to the east. Therefore, Ottoman Algeria, which contained few extensive, original, or long-lived Muslim dynasties, was not nearly as predisposed to developing political nationalism as was Tunisia during the first decades of the 19th century.

French Algeria

The conquest of Algeria

Modern Algeria can be understood only by examining the period—nearly a century and a half—that the country was under French colonial rule. The customary beginning date is in April 1827, when Ḥusayn, the last Ottoman provincial ruler, or dey, of Algiers, angrily struck the French consul with a fly whisk. This incident was a manifest sign of the dey’s anger toward the French consul, a culmination of what had soured Franco-Algerian relations in the preceding years: France’s large and unpaid debt. That same year the French minister of war had written that the conquest of Algeria would be an effective and useful means of providing employment for veterans of the Napoleonic wars.

The conquest of Algeria began three years later. The government of the dey proved no match for the French army that landed on July 5, 1830, near Algiers. Ḥusayn accepted the French offer of exile after a brief military encounter. After his departure, and in violation of agreements that had been made, the French seized private and religious buildings, looted possessions mainly in and around Algiers, and seized a vast portion of the country’s arable land. The three-century-long period of Algerian history as an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire had ended.

The French government thought that a quick victory abroad might create enough popularity at home to enable it to win the upcoming elections. Instead, only days after the French victory in Algeria, the July Revolution forced King Charles X from the throne in favour of Louis-Philippe. Although those who led the July Revolution in France had cynically dismissed the campaign in Algeria as foreign adventurism to cover up oppression at home, they were reluctant to simply withdraw. Various alternatives were considered, including an early ill-fated plan to establish Tunisian princes in parts of Algeria as rulers under French patronage. The French general, Bertrand Clauzel, signed two treaties with the bey of Tunis, one of which offered him the right to keep territories conceded to him in exchange for annual payments. Because the treaty was not communicated officially to the government in Paris, however, the bey considered this proof of French duplicity and refused the offer.

The first few years of colonial rule were characterized by numerous changes in the French command, and the military campaign began to prove extremely arduous and costly. The towns of the Mitidja Plain—just outside Algiers—and neighbouring cities fell first to the French. General Camille Trézel captured Bejaïa in the east in 1833 after a naval bombardment. The French took Mers el-Kebir in 1830 and entered Oran in 1831, but they faced stiffer opposition from the Sufi brotherhood leader, Emir Abdelkader (ʿAbd al-Qādir ibn Muḥyī al-Dīn), in the west. Because towns and cities were plundered and massacres of civilian populations were widespread, the French government sent a royal commission to the colony to examine the situation.

During their campaign against Abdelkader, the French agreed to a truce and signed two agreements with him. The treaty signed between General Louis-Alexis Desmichels and Abdelkader in 1834 included two versions, one of which made major concessions to Abdelkader again without the consent or knowledge of the French government. This miscommunication led to a breach of the agreement when the French moved through territory belonging to the emir. Abdelkader responded with a counterattack in 1839 and drove the French back to Algiers and the coast.

France decided at that point to wage an all-out war. Led by General (later Marshal) Thomas-Robert Bugeaud, the campaign of conquest eventually brought one-third of the total French army strength (more than 100,000 troops) to Algeria. The new military campaign and the initial onslaught caused widespread devastation to the Algerians and to their crops and livestock. Abdelkader’s hit-and-run tactics failed, and he was forced to surrender in 1847. He was exiled to France but later was permitted to settle with his family in Damascus, Syria, where he and his followers saved the lives of many Christians during the 1860 massacres. Respected even by his opponents as the founder of the modern Algerian state, Abdelkader became, and has remained, the personification of Algerian national resistance to foreign domination.

Abdelkader’s defeat marked the end of what might be called resistance on a national scale, but smaller French operations continued, such as the occupation of the Saharan oases (Zaatcha in 1849, Nara in 1850, and Ouargla in 1852). The eastern Kabylia region was subdued only in 1857, while the final major Kabylia uprising of Muḥammad al-Muqrānī was suppressed in 1871. The Saharan regions of Touat and Gourara, which were at that time Moroccan spheres of influence, were occupied in 1900; the Tindouf area, previously regarded as Moroccan rather than Algerian, became part of Algeria only after the French occupation of the Anti-Atlas in 1934.

Colonial rule

The manner in which French rule was established in Algeria during the years 1830–47 laid the groundwork for a pattern of rule that French Algeria would maintain until independence. It was characterized by a tradition of violence and mutual incomprehension between the rulers and the ruled; the French politician and historian Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that colonization had made Muslim society more barbaric than it was before the French arrived. There was a relative absence of well-established native mediators between the French rulers and the mass population, and an ever-growing French settler population (the colons, also known as pieds noirs) demanded the privileges of a ruling minority in the name of French democracy. When Algeria eventually became a part of France juridically, that only added to the power of the colons, who sent delegates to the French parliament. They accounted for roughly one-tenth of the total population from the late 19th century until the end of French rule.

Settler domination of Algeria was not secured, however, until the fall of Napoleon III in 1870 and the rise of the Third Republic in France. Until then Algeria remained largely under military administration, and the governor-general of Algeria was almost invariably a military officer until the 1880s. Most Algerians—excluding the colons—were subject to rule by military officers organized into Arab Bureaus, whose members were officers with an intimate knowledge of local affairs and of the language of the people but with no direct financial interest in the colony. The officers, therefore, often sympathized with the outlook of the people they administered rather than with the demands of the European colonists. The paradox of French Algeria was that despotic and military rule offered the native Algerians a better situation than did civilian and democratic government.

A large-scale program of confiscating cultivable land, after resistance had been crushed, made colonization possible. Settler colonization was of mixed European origin—mainly Spanish in and around Oran and French, Italian, and Maltese in the centre and east. The presence of the non-French settlers was officially regarded with alarm for quite a while, but the influence of French education, the Muslim environment, and the Algerian climate eventually created in the non-French a European-Algerian subnational sentiment. This would probably have resulted, in time, in a movement to create an independent state if Algeria had been situated farther away from Paris and if the settlers had not feared the potential strength of the Muslim majority.

After the overthrow of Louis-Philippe’s regime in 1848, the settlers succeeded in having the territory declared French; the former Turkish provinces were converted into departments on the French model, while colonization progressed with renewed energy. With the establishment of the French Second Empire in 1852, responsibility for Algeria was transferred from Algiers to a minister in Paris, but the emperor, Napoleon III, soon reversed this disposition. While expressing the hope that an increased number of settlers would forever keep Algeria French, he also declared that France’s first duty was to the three million Arabs. He declared, with considerable accuracy, that Algeria was “not a French province but an Arab country, a European colony, and a French camp.” This attitude aroused certain hopes among Algerians, but they were destroyed by the emperor’s downfall in 1870. After France’s defeat in the Franco-German War, settlers felt they could finally gain more land. Spurred on by this and by years of droughts and famines, Algerians united in 1871 under Muḥammad al-Muqrānī in the last major Kabylia uprising. Its brutal suppression by French forces was followed by the appropriation of another large segment of territory, which provided land for European refugees from Alsace. Much land was also acquired by the French through loopholes in laws originally designed to protect tribal property. Notable among these is the sénatus-consulte of 1863, which broke up tribal lands and allowed settlers to acquire vast areas formerly secured under tribal law. Following the loss of this territory, Algerian peasants moved to marginal lands and in the vicinity of forests; their presence in these areas set in motion the widespread environmental degradation that has affected Algeria since then.

It is difficult to gauge in human terms the losses suffered by Algerians during the early years of the French occupation. Estimates of the number of those dead from disease and starvation and as a direct result of warfare during the early years of colonization vary considerably, but the most reliable ones indicate that the native population of Algeria fell by nearly one-third in the years between the French invasion and the end of fighting in the mid-1870s.

Gradually the European population established nearly total political, economic, and social domination over the country and its native inhabitants. At the same time, new lines of communication, hospitals and medical services, and educational facilities became more widely available to Europeans, though they were dispensed to a limited extent—and in the French language—to Algerians. Settlers owned most Western dwellings, Western-style farms, businesses, and workshops. Only primary education was available to Algerians, and only in towns and cities, and there were limited prospects for higher education. Because employment was concentrated mainly in urban settlements, underemployment and chronic unemployment disproportionately affected Muslims, who lived mostly in rural and semirural areas.

For the Algerians service in the French army and in French factories during World War I was an eye-opening experience. Some 200,000 fought for France during the war, and more than one-third of the male Algerians between the ages of 20 and 40 resided in France during that time. When peace returned, some 70,000 Algerians remained in France and, by living frugally, were able to support many thousands of their relatives in Algeria.

Nationalist movements

Algerian nationalism developed out of the efforts of three different groups. The first consisted of Algerians who had gained access to French education and earned their living in the French sector. Often called assimilationists, they pursued gradualist, reformist tactics, shunned illegal actions, and were prepared to consider permanent union with France if the rights of Frenchmen could be extended to native Algerians. This group, originating from the period before World War I, was loosely organized under the name Young Algerians and included (in the 1920s) Khaled Ben Hachemi (“Emir Khaled”), who was the grandson of Abdelkader, and (in the 1930s) Ferhat Abbas, who later became the first premier of the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic.

The second group consisted of Muslim reformers who were inspired by the religious Salafī movement founded in the late 19th century in Egypt by Sheikh Muḥammad ʿAbduh. The Association of Algerian Muslim ʿUlamāʾ (Association des Uléma Musulmans Algériens; AUMA) was organized in 1931 under the leadership of Sheikh ʿAbd al-Hamid Ben Badis. This group was not a political party, but it fostered a strong sense of Muslim Algerian nationality among the Algerian masses.

The third group was more proletarian and radical. It was organized among Algerian workers in France in the 1920s under the leadership of Ahmed Messali Hadj and later gained wide support in Algeria. Preaching a nationalism without nuance, Messali Hadj was bound to appeal to Algerians, who fully recognized their deprivation. Messali Hadj’s strongly nationalistic stance, or even the more muted position of Ben Badis, could have been checked by such gradualist reformers as Ferhat Abbas if only they had been able to show that step-by-step decolonization was possible. Several efforts to liberalize the treatment of native Algerians, promoted by French reformist groups in collaboration with Algerian reformists in the first half of the 20th century, came too late to stem the radical tide.

One such effort, the Blum-Viollette proposal (named for the French premier and the former governor-general of Algeria), was introduced during the Popular Front government in France (1936–37). It would have allowed a very small number of Algerians to obtain full French citizenship without forcing them to relinquish their right to be judged by Muslim law on matters of personal status (e.g., marriage, inheritance, divorce, and child custody). The proposal was, therefore, a potential breakthrough because this issue had been shrewdly exploited by the settler population, who understood that most Algerians did not want to abandon this right. The small number of Algerians who would have received full French citizenship—the educated, veterans of French military service, and other narrowly defined groups—could then have been gradually increased in later years. Settler opposition to the measure was so fierce, however, that the project was never even brought to a vote in the French Chamber of Deputies. Many Algerians began to feel that organized violence was the only option, since all peaceful means for resolving the problems of colonial rule for the majority of the population had been denied. The group that inherited this mission, the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale; FLN), grew out of Messali Hadj’s organization, later absorbing many adherents of the other two nationalist groups.

People of Algeria

Ethnic groups

More than three-fourths of the country is ethnically Arab, though most Algerians are descendants of ancient Amazigh groups who mixed with various invading peoples from the Arab Middle East, southern Europe, and sub-Saharan Africa. Arab invasions in the 8th and 11th centuries brought only limited numbers of new people to the region but resulted in the extensive Arabization and Islamization of the indigenous Amazigh population. Some one-fifth of the Algerians now consider themselves Amazigh, of whom the Kabyle Imazighen (plural of Amazigh), occupying the mountainous area east of Algiers, form the largest group. Other Amazigh groups are the Shawia (Chaouïa), who live primarily in the Aurès Mountains; the Mʾzabites, a sedentary group descended from the 9th-century Ibāḍī followers of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Rustam, who inhabit the northern edge of the desert; and the Tuareg nomads of the Saharan Ahaggar region. Nearly all the European settlers—mainly French, Italian, and Maltese nationals, who formed a sizable minority in the colonial period—have left the country.

Languages

Arabic became the official national language of Algeria in 1990, and most Algerians speak one of several dialects of vernacular Arabic. These are generally similar to dialects spoken in adjacent areas of Morocco and Tunisia. Modern Standard Arabic is taught in schools. The Amazigh language (Tamazight)—in several geographic dialects—is spoken by Algeria’s ethnic Imazighen, though most are also bilingual in Arabic.

Algeria’s official policy of “Arabization” since independence, which aims to promote indigenous Arabic and Islamic cultural values throughout society, has resulted in the replacement of French by Arabic as the national medium and, in particular, as the primary language of instruction in primary and secondary schools. Some Amazigh groups have strongly resisted this policy, fearing domination by the Arabic-speaking majority. The Amazigh language was granted the status of a national language in 2002 and was upgraded to an official language in 2016.

Religion

Most Algerians, both Arab and Amazigh, are SunniMuslims of the Mālikī rite. A source of unity and cultural identity, Islam provides valuable links with the wider Islamic world as well. In the struggle against French rule, Islam became an integral part of Algerian nationalism. Alongside the more traditional institutions of the mosques and madrasahs (religious schools), Islam has possessed from its outset a deep mysticism, which has manifested itself in various, often culturally unique, forms. A distinctive North African facet of this tradition, stemming from Islamic folk practices and Sufi teaching, is the important role played by marabouts.

These saintly individuals were widely held to possess special powers and were venerated locally as teachers, healers, and spiritual leaders. Marabouts frequently formed extensive brotherhoods and at various times would take up the sword in defense of their religion and country (as did their namesakes, the al-Murābiṭūn; see Almoravids). In more peaceful times these local religious icons would practice a type of Islam that stressed local custom and direct spiritual insight as much as Qurʾānic teachings. Their independence was often perceived as a threat to established authority, and Islamic reformers and state bodies have historically sought to restrict the growth of marabout influence.

While Algeria’s post independence governments have confirmed the country’s Islamic heritage, their policies have often encouraged secular developments. Islamic fundamentalism has been increasing in strength since the late 1970s in reaction to this. Muslim extremist groups periodically have clashed with both left-wing students and emancipated women’s groups, while fundamentalist imams (prayer leaders) have gained influence in many of the country’s major mosques.

Cultural Life of Algeria

Cultural milieu

Algerian culture and society were profoundly affected by 130 years of colonial rule, by the bitter independence struggle, and by the subsequent broad mobilization policies of postindependence regimes. A transient, nearly rootless society has emerged, whose cultural continuity has been deeply undermined. Seemingly, only deep religious faith and belief in the nation’s populist ideology have prevented complete social disintegration. There has been a contradiction, however, between the government’s various populist policies—which have called for the radical modernization of society as well as the cultivation of the country’s Arab Islamic heritage—and traditional family structure. Although Algeria’s cities have become centres for this cultural confrontation, even remote areas of the countryside have seen the state take on roles traditionally filled by the extended family or clan. Algerians have thus been caught between a tradition that no longer commands their total loyalty and a modernism that is attractive yet fails to satisfy their psychological and spiritual needs. Only the more isolated Amazigh groups, such as the Saharan Mʾzabites and Tuareg, have managed to some degree to escape these conflicting pressures.

As is true elsewhere in North Africa, Algeria has experienced a dislocating clash between traditional and mass global culture, with Hollywood films and Western popular music commanding the attention of the young at the expense of indigenous forms of artistic and cultural expression. This clash is the subject of much fiery commentary from conservative Muslim clergymen, whose influence has grown with the rise of Islamic extremism. Extremists have opposed secular values in art and culture and have targeted prominent Algerian authors, playwrights, musicians, and artists—including the director of the National Museum, who was assassinated in 1995; novelist Tahar Djaout, who was murdered in 1993; and the well-known Amazigh musician Lounès Matoub, who was assassinated in 1998. As a result, much of the country’s cultural elite has left the country to work abroad, mostly in France.

Daily life and social customs

Despite efforts to modernize Algerian society, the pull of traditional values remains strong. Whether in the city or countryside, the daily life of the average Algerian is permeated with the atmosphere of Islam, which has become identified with the concept of an autonomous Algerian people and of resistance to what many Algerians perceive as a continued Western imperialism. Practiced largely as a set of social prescriptions and ethical attitudes, Islam in Algeria has more characteristically been identified with supporting traditional values than serving a revolutionary ideology.

In particular, the influential Muslim clergy has opposed the emancipation of women. Algerians traditionally consider the family—headed by the husband—to be the basic unit of society, and women are expected to be obedient and provide support to their husbands. As in most parts of the Arab world, men and women in Algeria generally have constituted two separate societies, each with its own attitudes and values. Daily activities and social interaction normally take place only between members of the same gender. Marriage in this milieu is generally considered a family affair rather than a matter of personal preference, and parents typically arrange marriages for their children, although this custom is declining as Algerian women take on a greater role in political and economic life. Some women continue to wear veils in public because traditionally minded Algerian Muslims consider it improper for a woman to be seen by men to whom she is not related. The practice of veiling has in fact increased since independence, especially in urban areas, where there is a greater chance of contact with nonrelatives.

Algerian cuisine, like that of most North African countries, is heavily influenced by Arab, Amazigh, Turkish, and French culinary traditions. Couscous, a semolina-based pasta customarily served with a meat and vegetable stew, is the traditional staple. Although Western-style dishes, such as pizza and other fast foods, are popular and Algeria imports large quantities of foodstuffs, traditional products of Algerian agriculture remain the country’s best-liked. Mutton, lamb, and poultry are still the meat dishes of choice; favourite desserts rely heavily on native-grown figs, dates, and almonds and locally produced honey; and couscous and unleavened breads accompany virtually every meal. Brik (a meat pastry), merguez (beef or lamb sausage), and lamb or chicken stew are among the many local dishes served in homes and restaurants. As is the case in the Middle East, strong, sweet Turkish-style coffee is the beverage of choice at social gatherings, and mint tea is a favourite.

Algeria observes several religious and secular holidays, including the important Islamic festivals and commemorations such as Ramadan, the two ʿīds (festivals), Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, and mawlid (the Prophet’s birthday), as well as national holidays such as Independence Day (July 5).

The arts

Various types of music are native to Algeria. One of the most popular, originating in the western part of the country, is raï (from Arabic raʾy, meaning “opinion” or “view”), which combines varying instrumentation with simple poetic lyrics. Both men and women are free to express themselves in this style. One especially popular Algerian singer of raï, Khaled, has exported this music to Europe and the United States, but he and other popular musicians such as Cheb Mami have been targets of Islamic extremists. Wahrani (the music of Oran), another style, blends raï with classical Algerian music of the Arab-Andalusian tradition.

Algeria has produced many important writers. Some, such as the Nobel Prize winner Albert Camus and his contemporary Jean Sénac, were French, although their work was influenced by the many years they spent in Algeria. The writing of Henri Kréa reflects the two worlds he inhabited as the son of a French father and an Algerian mother. ʿAbd al-Hamid Benhadugah is the father of modern Arabic literature in Algeria, while Jean Amrouche is considered the foremost poet of the first generation of North African writers who wrote in French; his younger sister Marguerite Taos Amrouche was a noted singer and writer. The work of Mouloud Feraoun reflects Amazigh life. Mohammed Dib, Malek Haddad, Tahar Djaout, Mourad Bourboune, Rachid Boudjedra, and Assia Djebar have all written about contemporary life in Algeria, with Djebar reflecting on this from a woman’s perspective.

Algeria has maintained a lively film industry, although filmmakers frequently have endured bouts with government pressure and, more recently, have been subjected to intimidation by Islamic extremists. The first major postcolonial production was the celebrated film La battaglia di Algeri (1966; The Battle of Algiers). Though written and directed by an Italian, Gillo Pontecorvo, the work—a stark factual retelling of urban warfare during the revolution—was supported by the Algerian government and was cast with numerous nonactors, including many residents of Algiers who participated in the actual events. The following year Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina directed Rīḥ al-Awras (1966; The Winds of the Aures), the first work by an Algerian to win international acclaim. His Chronique des annees de braise (1975; Chronicle of the Year of Embers), another gritty tale of the revolution, was awarded the Palme d’Or at the Cannes film festival nearly a decade later. Several films by the celebrated director Merzak Allouache, including Omar Gatlato (1976) and Bāb al-wād al-ḥawmah (1994; Bab El-Oued City), which deal with the complexity of daily life in urban Algeria, have received international recognition. Additionally, director Bourlem Guerdjou examined the difficulties of the Algerian diaspora in France in his award-winning Vivre au paradis (1997; Living in Paradise).

Cultural institutions

Algeria has a number of fine museums, most of which are located in the capital and are administered by the Office of Cultural Heritage (1901). The National Museum of Antiquities (1897) displays artifacts dating from the Roman and Islamic periods. The National Fine Arts Museum of Algiers (1930) houses statues and paintings, including some lesser works of well-known European masters, and the Bardo Museum (1930) specializes in history and ethnography. Most other cultural institutions also are found in Algiers, including the National Archives of Algeria (1971), the National Library (1835), and the Algerian Historical Society (1963).

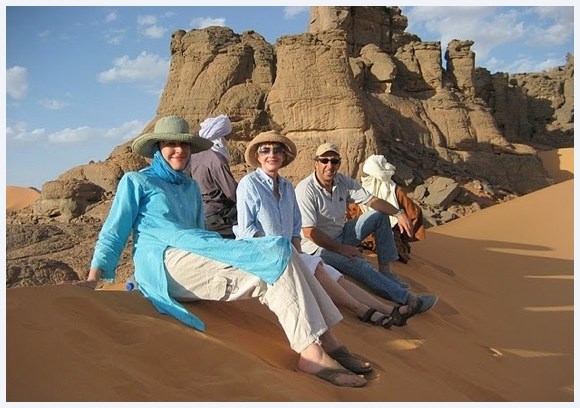

Undiscovered Algeria

Tourism in Algeria is an opportunity you can’t miss. Are you looking to experience one of North Africa’s least visited countries in the safety and comfort of a private tour? Remaining relatively undiscovered with few crowds, Algeria is a fascinating land with incredible sites and scenery. We will plan your authentic Algeria tour from 3-star standard accommodations to 5-star luxury tours.

All of our tours are accompanied by an expert Algerian tour manager or guide. Our guides provide unbeatable insights into the history and culture of Algeria so that you experience the ‘real’ Algeria. We understand the security situation and will make sure you are well taken care of during your holiday tour.

There is something for everyone in Algeria so come and wander through Roman ruins, experience the UNESCO World Heritage Kasbah in Algiers, learn about life in an ancient Oasis, and more. We can custom design your tour package to provide unbeatable day or weekend excursions to breath-taking sites.