Yes, it's Jordan

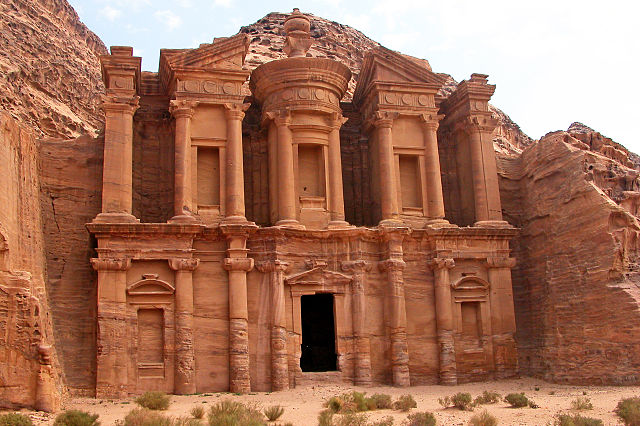

Jordan, an Arab nation on the east bank of the Jordan River, is defined by ancient monuments, nature reserves and seaside resorts. It’s home to the famed archaeological site of Petra, the Nabatean capital dating to around 300 B.C. Set in a narrow valley with tombs, temples and monuments carved into the surrounding pink sandstone cliffs, Petra earns its nickname, the “Rose City.”

History of Jordan

Jordan occupies an area rich in archaeological remains and religious traditions. The Jordanian desert was home to hunters from the Early Paleolithic Period; their flint tools have been found widely distributed throughout the region. In the southeastern part of the country, at Mount Al-Ṭubayq, rock carvings date from several prehistoric periods, the earliest of which have been attributed to the Paleolithic-Mesolithic era. The site at Tulaylāt al-Ghassūl in the Jordan Valley of a well-built village with painted plaster walls may represent transitional developments from the Neolithic to the Chalcolithic period.

The Early Bronze Age (c. 3000–2100 BC) is marked by deposits at the base of Dhībān. Although many sites have been found in the northern portion of the country, few have been excavated, and little evidence of settlement in this period is found south of Al-Shawbak. The region’s early Bronze Age culture was terminated by a nomadic invasion that destroyed the principal towns and villages, marking the end of an apparently peaceful period of development. Security was not reestablished until the Egyptians arrived after 1580 BC. It was once believed that the area was unoccupied from 1900 to 1300 BC, but a systematic archaeological survey has shown that the country had a settled population throughout the period. This was confirmed by the discovery of a small temple at Amman with Egyptian, Mycenaean, and Cypriot imported objects.

People of Jordan

Ethnic groups

The overwhelming majority of the people are Arabs, principally Jordanians and Palestinians; there is also a significant minority of Bedouin, who were by far the largest indigenous group before the influx of Palestinians following the Arab-Israeli wars of 1948–49 and 1967. Jordanians of Bedouin heritage remain committed to the Hāshimite regime, which has ruled the country since 1923, despite having become a minority there. Although the Palestinian population is often critical of the monarchy, Jordan is the only Arab country to grant wide-scale citizenship to Palestinian refugees. Other minorities include a sizeable number of Syrian refugees who fled to Jordan because of the Syrian Civil War, as well as a number of Iraqis who fled to Jordan as a result of the Persian Gulf War and Iraq War. There are also smaller Circassian (known locally as Cherkess or Jarkas) and Armenian communities. A small number of Turkmen (who speak either an ancient form of the Turkmen language or the Azeri language) also reside in Jordan.

The indigenous Arabs, whether Muslim or Christian, used to trace their ancestry from the northern Arabian Qaysī (Maʿddī, Nizārī, ʿAdnānī, or Ismāʿīlī) tribes or from the southern Arabian Yamanī (Banū Kalb or Qaḥṭānī) groups. Only a few tribes and towns have continued to observe this Qaysī-Yamanī division—a pre-Islamic split that was once an important, although broad, source of social identity as well as a point of social friction and conflict.

Languages

Nearly all the people speak Arabic, the country’s official language. There are various dialects spoken, with local inflections and accents, but these are mutually intelligible and similar to the type of Levantine Arabic spoken in parts of Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria. There is, as in all parts of the Arab world, a significant difference between the written language—known as Modern Standard Arabic—and the colloquial, spoken form. The former is similar to Classical Arabic and is taught in school. Most Circassians have adopted Arabic in daily life, though some continue to speak Adyghe (one of the Caucasian languages). Armenian is also spoken in pockets, but bilingualism or outright assimilation to the Arabic language is common among all minorities.

Religion

Virtually the entire population is Sunni Muslim; Christians constitute most of the rest, of whom two-thirds adhere to the Greek Orthodox church. Other Christian groups include the Greek Catholics, also called the Melchites, or Catholics of the Byzantine rite, who recognize the supremacy of the Roman pope; the Roman Catholic community, headed by a pope-appointed patriarch; and the small Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch, or Syrian Jacobite Church, whose members use Syriac in their liturgy. Most non-Arab Christians are Armenians, and the majority belong to the Gregorian, or Armenian, Orthodox church, while the rest attend the Armenian Catholic Church. There are several Protestant denominations representing communities whose converts came almost entirely from other Christian sects.

The Druze, an offshoot of the Ismāʿīlī Shiʿi sect, number a few hundred and reside in and around Amman. About 1,000 Bahāʾī—who in the 19th century also split off from Shiʿi Islam—live in Al-ʿAdasiyyah in the Jordan Valley. The Armenians, Druze, and Bahāʾī are both religious and ethnic communities. The Circassians are mostly Sunni, and they along with the closely related Chechens (Shīshān)—a group numbering about 1,000, who are descendants of 19th-century immigrants from the Caucasus Mountains—make up the most important non-Arab minority.

Art & Culture of Jordan

The arts

Both private and governmental efforts have been made to foster the arts through various cultural centres, notably in Amman and Irbid, and through the establishment of art and cultural festivals throughout the country. Modernity has weakened the traditional Islamic injunction against the depiction of images of humans and animals; thus, in addition to traditional architecture, decorative design, and various handicrafts, it is possible to find non-utilitarian forms of both representational and abstract painting and sculpture. Elaborate calligraphy and geometric designs often enhance manuscripts and mosques. As in the rest of the region, the oral tradition is prominent in literary expression. Jordan’s most famous poet, Muṣṭafā Wahbah al-Ṭāl, ranks among the major Arab poets of the 20th century. After World War II a number of important poets and prose writers emerged, though few have achieved an international reputation.

Traditional visual arts survive in works of tapestry, embroidery, leather, pottery, and ceramics, and in the manufacture of wool and goat-hair rugs with varicoloured stripes; singing is also important, as is storytelling. Villagers have special songs for births, circumcisions, weddings, funerals, and harvesting. Several types of dabkah (group dances characterized by pounding feet on the floor to mark the rhythm) are danced on festive occasions, while the sahjah is a well-known Bedouin dance. The Circassian minority has a sword dance and several other Cossack dances. As part of its effort to preserve local performing arts, the government sponsors a national troupe that is regularly featured on state radio and television programs.

Jordan has a small film industry, and sites within the country, such as Petra and the Ramm valley, have served as locations for major foreign productions, such as director David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989).

Cultural Life

Daily life and social customs

Jordan is an integral part of the Arab world and thus shares a cultural tradition common to the region. The family is of central importance to Jordanian life. Although their numbers have fallen as many have settled and adopted urban culture, the rural Bedouin population still follows a more traditional way of life, preserving customs passed down for generations. Village life revolves around the extended family, agriculture, and hospitality; modernity exists only in the form of a motorized vehicle for transportation. Urban-dwelling Jordanians, on the other hand, enjoy all aspects of modern, popular culture, from theatrical productions and musical concerts to operas and ballet performances. Most major towns have movie theatres that offer both Arab and foreign films. Younger Jordanians frequent Internet cafés in the capital, where espresso is served at computer terminals.

The country’s cuisine features dishes using beans, olive oil, yogurt, and garlic. Jordan’s two most popular dishes are msakhan, lamb or mutton and rice with a yogurt sauce, and mansaf, chicken cooked with onions, which are both served on holidays and on special family occasions. Daily fare includes khubz (flatbread) with vegetable dips, grilled meats, and stews, served with sweet tea or coffee flavoured with cardamom.

Holidays that are celebrated in the kingdom include the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday, the two ʿīds (festivals; ʿĪd al-Fiṭr and ʿĪd al-Aḍḥā), and other major Islamic festivals, along with secular events such as Independence Day and the birthday of the late King Ḥussein.

Dead Sea!

A spectacular natural wonder the Dead Sea is perfect for religious tourism and fun in the sun with the family. With its mix of beach living and religious history you can soak up the sun while Biblical scholars can get their daily dose of religious history. The leading attraction at the Dead Sea is the warm, soothing, super salty water itself – some ten times saltier than sea water, and rich in chloride salts of magnesium, sodium, potassium, bromine and several others. The unusually warm, incredibly buoyant and mineral-rich waters have attracted visitors since ancient times, including King Herod the Great and the beautiful Egyptian Queen, Cleopatra. All of whom have luxuriated in the Dead Sea’s rich, black, stimulating mud and floated effortlessly on their backs while soaking up the water’s healthy minerals along with the gently diffused rays of the Jordanian sun.